Ready, set, Portrait!

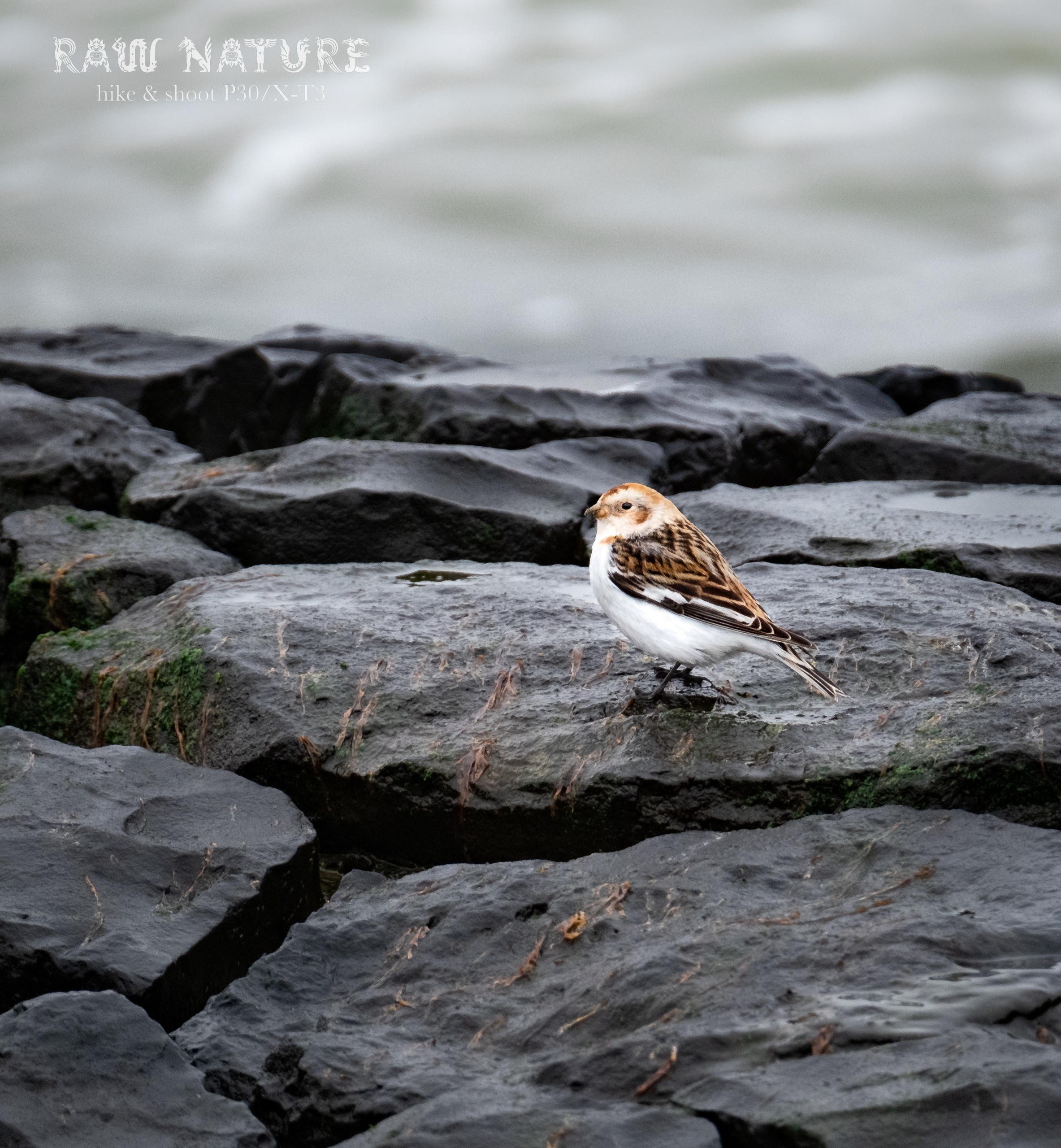

Portraiture counts among the most classical disciplines in photography. A good portrait captures the character of the subject, requiring both knowledges of the subject and time. Yet, it is precisely the factor of time that we generally lack in most of our encounters with wildlife. They tend to be brief and dynamic, as the animal notices us before we notice them.

Therefore, one of the best ways to obtain nice portraits of wildlife, is to have a good old-fashioned stake-out. Long, sedentary hours spent at a hide-out in the woods, where we let the subject come to us, instead of actively seeking it out. In the best cases, the animals remain blissfully unaware of our presence. We can start to study their approach patterns, and think about where and when we would like to take the shot that we are looking for, including some of the environment for composition.

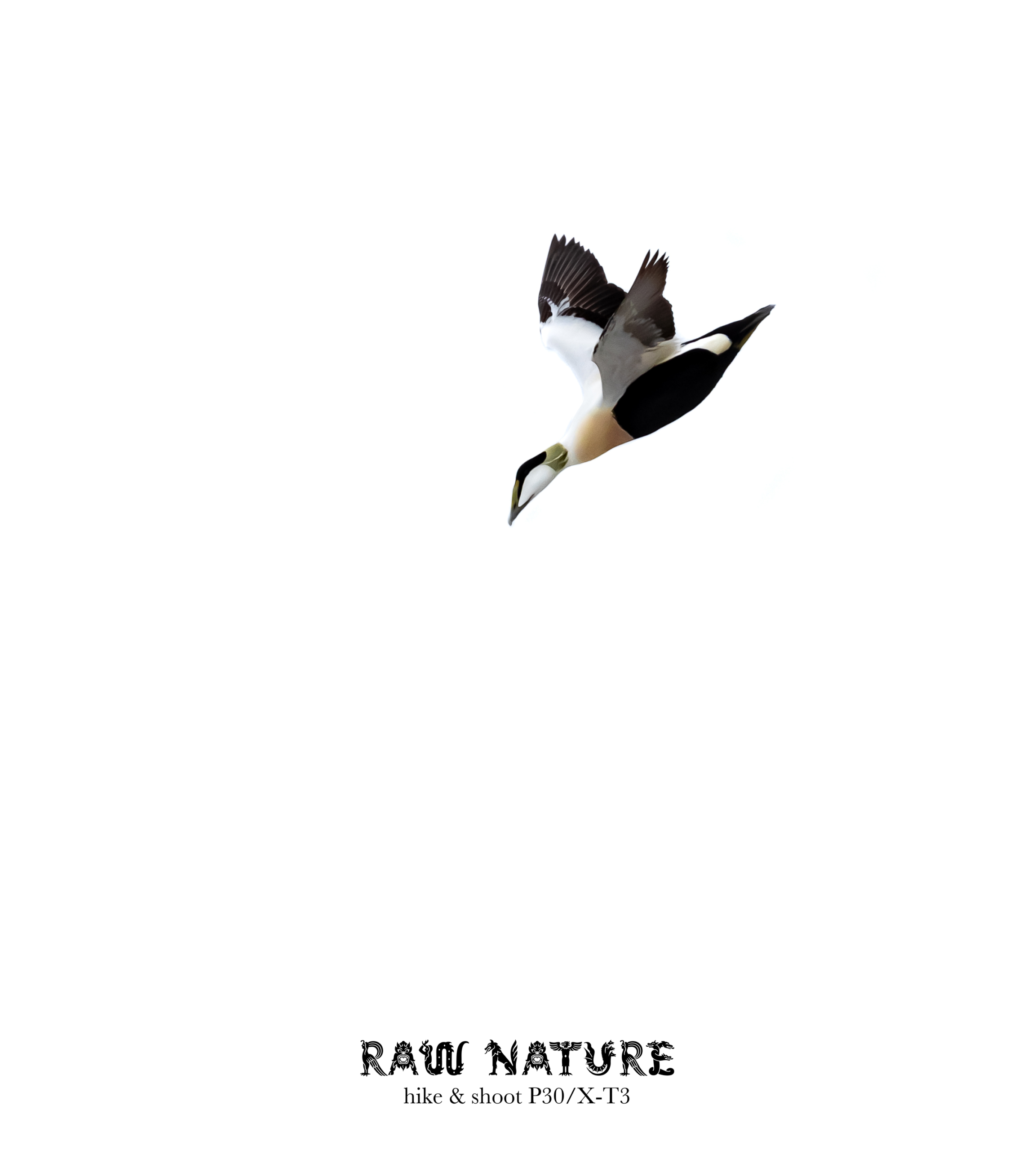

Such classic side or front shots have a clear, crisp and appealing charachter. Yet sometimes their conventional nature just doesn’t fit with the subject, or it’s just good plain old fun to mix expectations up a bit!